NIH-funded study establishes genomic data set on Lassa virus

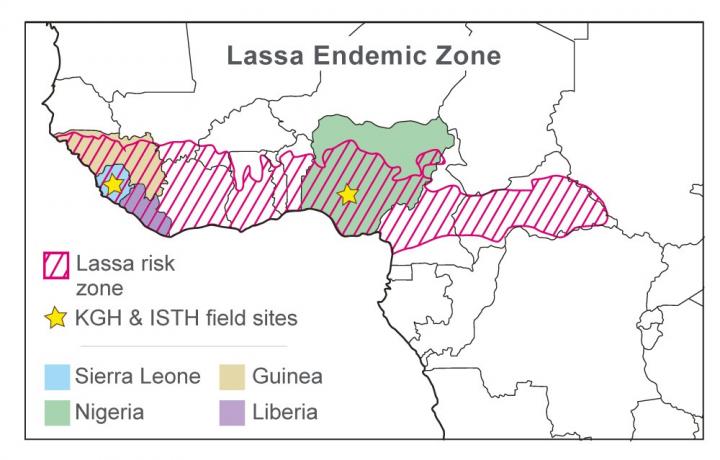

An international team of researchers has developed the largest genomic data set in the world on Lassa virus (LASV). The new genomic catalog contains nearly 200 viral genomes collected from patient samples in Sierra Leone and Nigeria, as well as field samples from the major animal reservoir, or host, of Lassa virus--the rodent Mastomys natalensis, also called the multimammate rat. The researchers show that LASV strains cluster into four major groups based on geographic location, with three in Nigeria and one in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. Although Lassa fever was first described in modern-day Nigeria in 1969, the current study also suggests that these four LASV strains originated from a common ancestral virus more than 1,000 years ago and spread across West Africa within the last several hundred years.

Prior to the study, data from only 12 complete genomes of LASV were available, despite the virus' endemic presence in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa. The new catalog of data provides a foundation for ongoing research on LASV and offers insight into the virus' origins and transmission. The study is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The data set is publicly accessible at the National Center for Biotechnology Information's BioProject website under PRJNA254017 .

While Lassa fever is often mild, the disease can be severe with signs and symptoms similar to those of Ebola virus disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, LASV causes roughly 100,000 to 300,000 cases of Lassa fever each year in West Africa, with approximately 5,000 deaths; as many as 10 to 16 percent of hospital admissions in some areas of West Africa may be due to Lassa fever. No cure or vaccine is available for Lassa fever, but the antiviral drug ribavirin may help patients if taken early in the course of the disease. Infections in people mainly occur through exposure to infected rodents or their secretions, and less commonly, between people through direct contact with bodily fluids.

"Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases like Lassa fever are global health challenges, and the NIH has a long history of investing in global research to improve the health of people in the United States and around the world," said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. "The new Lassa virus data set will be valuable for understanding Lassa virus and developing medical countermeasures such as diagnostics, therapies, and

vaccines."

In the new study, researchers analyzed samples collected from the Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone and the Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital in Nigeria between 2008 and 2013. The genomic data set, with samples from people and the animal host, confirmed that viral transmission mainly occurs from rodent to human, and not between people. Previous estimates suggested that up to 20 percent of LASV infections were caused by human-to-human transmission, but the new analysis indicates that human-to-human transmissions are likely much lower.

The study offers new information about LASV mutations and its replication in infected individuals that may help scientists understand how the virus causes infection and evades the immune response, and why clinical outcomes can differ so widely.

Source: NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Microbiology

-

New genus of bacteria found living inside hydraulic fracturing wells

-

New clues found to how 'cruise-ship' virus gets inside cells

-

Discovery of new hepatitis C virus mechanism

-

Mouse antibodies pinpoint Zika's weak spots

-

Cracking the mystery of Zika virus replication

-

Researchers map Zika's routes to the developing fetus

-

How a cold gets into cells

-

Protein structure paves the way for new broad spectrum antifungals

-

The Institut Pasteur in French Guiana publishes the first complete genome sequence of the Zika virus

-

Penn study reveals how fish control microbes through their gills

-

Bacteria take 'RNA mug shots' of threatening viruses

-

Algae use their 'tails' to gallop and trot like quadrupeds

-

Discovery shows how herpes simplex virus reactivates in neurons to trigger disease

-

Intestinal worms 'talk' to gut bacteria to boost immune system

-

Deep-sea bacteria could help neutralize greenhouse gas, researchers find